Duidelijke betekenis van het merk

Gerecht EU 13 juni 2012, zaak T-342/10 (Hartmann tegen OHIM/Mölnlycke Health Care)

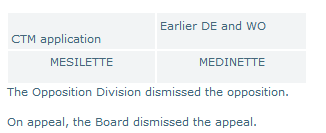

Gemeenschapsmerkenrecht. In de oppositieprocedure komt aanvrager van het woordmerk MESILETTE (klasse 5) de houder van het Duitse en internationale woordmerk MEDINETTE tegen. De oppositieafdeling wijst de oppositie af, het beroep wordt verworpen. Middel: verwarringsgevaar is onjuist beoordeeld.

Gemeenschapsmerkenrecht. In de oppositieprocedure komt aanvrager van het woordmerk MESILETTE (klasse 5) de houder van het Duitse en internationale woordmerk MEDINETTE tegen. De oppositieafdeling wijst de oppositie af, het beroep wordt verworpen. Middel: verwarringsgevaar is onjuist beoordeeld.

Gerecht EU vernietigt de uitspraak van de Kamer van Beroep. Ondanks de visuele en fonetische overeenkomsten bestaat er een verschil tussen de twee merken MEDINETTE en MESILETTE. Dit verschil bestaat uit het feit dat voor het publiek duidelijk is dat het eerste merk naar de medische sector verwijst (middels: 'medi'), waardoor het een duidelijke betekenis heeft voor het publiek, dit gedlt niet voor MESILETTE. Er is dus een duidelijke betekenis van het merk, dat voorkomt dat er een verwarringsgevaar is.

31 The conclusion that there is an average degree of visual and phonetic similarity between the signs at issue cannot be weakened by the finding of the Board of Appeal that, because of the element ‘medi’ in the earlier marks which alludes to the medical sector, less importance must be accorded to it in the context of the assessment of similarities since the relevant public will focus most of its attention on the suffix ‘nette’. Even if the element ‘medi’ refers to the medical sector, that fact could only have an effect in the context of the assessment of conceptual similarity. The descriptive character of a word element can have no relevance to the assessment of visual and phonetic similarities, where the only factors which must be taken into consideration are those capable of having a specific effect on visual and phonetic impressions (see, to that effect, judgment of 13 September 2010 in Case T 149/08 Abbott Laboratories v OHIM – aRigen (Sorvir), not published in the ECR, paragraph 37).

32 As regards the conceptual comparison of the signs at issue, it must be noted that conceptual differences may, to a large degree, counteract phonetic and visual similarities between the marks at issue, provided that at least one of those marks has, from the point of view of the relevant public, a clear and specific meaning, so that the public is capable of grasping it immediately (see, to that effect, Case C 16/06 P Éditions Albert René v OHIM [2008] ECR I 10053, paragraph 98, and judgment of 11 November 2009 in Case T 277/08 Bayer Healthcare v OHIM – Uriach-Aquilea OTC (CITRACAL), not published in the ECR, paragraph 53).

33 It should also be noted that, while the average consumer normally perceives a mark as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details (Case C 342/97 Lloyd Schuhfabrik Meyer [1999] ECR I 3819, paragraph 25), the fact remains that, when perceiving a word sign, he will break it down into elements which, for him, suggest a concrete meaning or which resemble words known to him (see, to that effect, Case T 256/04 Mundipharma v OHIM – Altana Pharma (RESPICUR) [2007] ECR II 449, paragraph 57, and CITRACAL, paragraph 55).

34 In the present case, the relevant public, because of its knowledge and experience, will generally be able to establish a conceptual link between the element ‘medi’ in the earlier marks and the medical sector (judgment of 6 October 2011 in Case T 247/10 medi v OHIM – Deutsche Medien Center (deutschemedi.de), not published in the ECR, paragraphs 41 and 42). As the Board of Appeal rightly found, the element ‘medi’ corresponds, for all the relevant languages, to the root of words clearly alluding to the medical sector: ‘Medikamente’ and ‘Medizin’ in German, ‘medicina’ in Hungarian, ‘medicína’ in Czech and Slovak, ‘medycyne’ in Polish, ‘medicina’ in Italian, ‘médicine’ in French, ‘medicinski’ and ‘medicina’ in Bulgarian; ‘medisch’ in Dutch and ‘medicament’ in Romanian.